My Life in New England

I’d like to start by talking about my life in New England. After my extensive trip across North and South America, I went back to Montreal to see what was going on and decide what to do next. Returning to work at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel was out of the question since I had left them once before, and they likely thought I would leave them again. But then a friend told me about a sous chef opening on Cape Cod. I got in touch with the management of the hotel, and a few days later, I arrived in Hyannis, MA, and started work the next day.

Parts of the hotel were still under construction, and we had a few months before the season started. However, the restaurant was open and served breakfast and lunch. The food was simple and typical of the 1970s East Coast cuisine: prime rib, ribeye steak, New York strip, filet mignon, veal piccata, and, of course, seafood like lobster—boiled or baked cod, stuffed sole, scallops, and shrimp. All in all, it was pretty bland and not the greatest cuisine. I kind of felt it was a wasteland of gastronomy. When I told my friends in Canada and Europe that I was going to the United States, they said, “What are you doing in that country? The only thing they have is frozen food.” Now, that’s not exactly true, but I also learned a lot here. I got my introduction to cooks who had never learned their trade. Some of these people even had other jobs during the season. Some could only cook breakfast or handle the salad station, while others were good sandwich makers or only knew how to boil or poach food. Some of these kids had just come out of school and had never worked in a real kitchen. For me, it was a nightmare.

Shortly after I arrived, the executive chef was fired, and I was asked to replace him. This was not exactly how I had dreamed of becoming an executive chef, and to make matters worse, within a few weeks, the banquet facility opened, and the kitchen equipment wasn’t even installed yet. I began to wonder about this hotel. The rooms used for banquets were also used for shows, and our first entertainer was Sammy Davis Jr. He had two shows a night and a cocktail show. How we managed to serve 1,000 people, I don’t know. Now, looking back, I can’t believe we did it.

Thank God I met a beautiful girl, and without her, I wonder if I would have stayed. To top everything off, the hotel messed up my paperwork, so in the fall, I had to leave the country and wait until my paperwork was sorted out. There’s not much to say about the culinary heights of my first experience as an executive chef. However, I made some great friends, John and Maxine, who were in their second year across the street at a restaurant called The Paddock. Ralph, their friend and my boss at the hotel, was also part of our circle, as was Gracian. We are all still around, except Ralph, who passed away. He was a hell of a guy. He loved women and lived a full life, being in the restaurant business, living in Key West right after the war during Hemingway’s time, owning a great place in New York City called Ralph’s, and running a restaurant on Long Island when these places were real instead of today’s mingling grounds of the rich. The stories I was told could fill a book. After all, concierges in Switzerland told me once, “If you ever get asked anything about our guests, your answer is always, ‘I am not aware of such things.’”

What can I say about John and Maxine? I worked with them the following season at The Paddock. It was their second or third season, and we became lifelong friends and the best partners I ever worked with. After all my travels in the United States, I eventually returned to the Cape, opened a restaurant with John, Maxine, and their sons, and that was the last time I ever worked in the restaurant business. After we sold it, I retired. I thought I had had enough, but then I got really bored. So that’s why I’m telling you all about my life, which you might find a little interesting.

Let me tell you about Cape Cod before I get into the cooking situation. Historic Cape Cod is an Eden-like peninsula, guarded by dangerous shoals. Cape Cod emerged from the junction of the last two glaciers of the last Ice Age thousands of years ago. It has evolved and eroded into a series of rolling hills and outwash plains, spilling northward toward Cape Cod Bay and southward toward Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket Sound. Seas like relentless bulldozers washed ashore unfathomable amounts of sand. The glacial silt and waves have smoothed the rough edges of these outermost shores into something that can rightly be called a work of art.

The best guess is that American Indians arrived on this newly formed land about 10,000 years ago, settling in areas across the Cape. There were many different tribes, and even the tribes had sub-tribes. I really don’t know all the different names of the tribes—they are very hard to pronounce—so I’m just going to let that go. Indian dominance of the Cape lasted for more than nine and a half millennia.

There are many tales of Norse explorers arriving in this area, but there has yet to be definitive proof of such exploration. One legend describes that around AD 986, Norsemen visited the Cape and the islands, though they did not make landfall. Bjarni Herjólfsson was the little-known Norse explorer who made this journey, and if the story is true, then he discovered America about 500 years before Columbus. Upon his return to his native Iceland—or was it actually Greenland?—he told the story, and it became incorporated into Norse lore to be retold for years to come. Listening to these tales was Leif Erikson, son of Erik the Red. Around the year 1000, Leif borrowed his father’s ship and sailed south past Newfoundland and Nova Scotia to arrive at what some historians believe was Cape Cod. The story goes that he sailed his vessel up a river that flowed in two directions—this was the Bass River—and made his camp at an inland lake where he could anchor his vessel. It was supposed to be Follins Pond at the head of the Bass River in Yarmouth and Dennis.

Whether you believe the tales or not, it is clear that American Indians were the sole inhabitants of this area until the early 1600s. The year 1602 saw a sail on the horizon growing larger as it approached—a sail representing the first of many to arrive along the shores over the next decades. It was English explorer Bartholomew Gosnold. After landing at a number of spots along the Cape and islands and discovering the treacherous shoals that gathered at the easternmost section of the Cape, Gosnold and his crew chose one of the Elizabeth Islands to establish their settlement. When that settlement failed shortly thereafter, four years later in October 1606, a French expedition arrived at what is now Stage Harbor in Chatham. On board were explorer Samuel de Champlain, Denis Hay, and Jean de Poutrincourt. A few days after their arrival, a battle was fought between the French and the local tribe, and with damage done to the crew, they left to explore other parts of North America.

For years after, other notable explorers such as Henry Hudson and John Smith avoided these shores, as tales of the battle at Stage Harbor no doubt had circulated. It was not until November 1620 that European explorers would try again to settle this virgin outpost. This was the month when the Mayflower arrived in what is today Provincetown. The vessel had been blown off course and landed well north of its intended destination of Virginia. The Pilgrims spent less than a month on the Cape, at one point stopping in Eastham for their first encounter with the Indians. They then raised anchor and made a short trek across Cape Cod Bay to Plymouth, where they would establish their permanent settlement. Yet the Pilgrims would return to Cape Cod again and again. Many were instrumental in preparing the way for the settlement of a number of the earliest towns. Each of these towns would develop its own independent history, carving out its own niche across Cape Cod.

Meanwhile, the American Indians were already in decline—epidemics just three or four years before the arrival of the Pilgrims had decimated their ranks considerably. Unwise to the laws of the new settlers, these Indians unwittingly handed over large tracts of land for a pittance, not realizing that the mark on the white man’s strange parchment was legal and binding. They did not understand the term “ownership” and thought that they were merely allowing the settlers to use their land. By the time they began to understand what was happening, it was too late.

Religion played a large role in the different towns. Most of the earliest settlers were Congregationalists, but there were also Quakers among them, and later Methodists and Baptists. These settlers left other places to land here in search of religious freedom. Many of them found themselves embroiled in the same old religious arguments. And when the settlers were not arguing about religion, they were squabbling over land—where one person’s boundary ended and another began. With the building of a meeting house and the hiring of a minister to preach, a handful of families would form an application for incorporation. The church-built incorporation spurred more settlements, and thus the towns were born, grew, and prospered.

Cape Cod has more than three and a half centuries of documented history. Each of the towns displays its history like a treasured heirloom—cemeteries, old churches, houses, and museums all help to preserve the stories that will never be forgotten, including how the land was stolen from the Indians. An old quote goes: The white settlers asked, “Who owns the land?” The Indians, perhaps not understanding the question and certainly not identifying with the European notion of ownership, replied, “Nobody.” So the settlers announced, in true Manifest Destiny mentality, “Then we own it,” and so began the settlements of the 15 towns on Cape Cod, each a bit different from the other, with their legends and stories.

All of them are worth a visit, and if you’d like to read about them, you can visit the town halls and find out how they started and became what they are today. If you ever go to the Cape, one thing you must do, besides visiting all the beautiful towns, is visit the Cape Cod National Seashore. A 40-mile strip of sea-pounded sand dunes has enjoyed federal protection only since 1961, thanks to longtime summer resident JFK. But in fact, precious little has changed since Henry David Thoreau roamed the area in the 1850s, describing it as a place where “one man can stand and put all America behind him.” From Chatham at the peninsula’s elbow in the south to the artsy end of the line, Provincetown at its northernmost tip, the solitary seashore of wide-open beaches, lighthouses, big waves, and dune grass is one of America’s most magnificent.

Over 43,000 acres of dramatic high dunes join the great sea in an ever-changing play of light. In autumn, one of the area’s nicest seasons, the Outer Cape is the flyway for more than 300 migratory species. The best way to get there is on Route 6A, once nothing more than a sandy Indian footpath, now a winding two-lane road that makes for a great day trip. This is a beautiful experience, which will be very memorable, and you definitely should do that if you’re there for a short time.

So, this is a little bit of history about Cape Cod and how I got there, and then I will tell you a little bit about my work there during the first two seasons. That’s a good opening that would have to be redone anyway.

Working and Living in Hyannis, MA

All right, I’ve told you a little bit about what Cape Cod is all about, and now I’d like to tell you what I actually did there. I worked at the Sheraton Hyannis Hotel and Resort. It is safe to say that the Hyannis Hotel and Resort is one of the premier hotel accommodations in Hyannis, located directly across the street from the Cape Cod Melody Tent, making it a convenient accommodation for the tent’s star performers. It is a full-service hotel with a conference center. It offers everything from concierge and shuttle services to a beautiful 60-foot indoor pool and a seafood cabana serving lunch and refreshments. Most of the hotel’s 224 rooms have views of the golf course or an attractive courtyard and offer double, king, or suite units. One thing you will definitely enjoy is the restaurant, as well as the Yacht Club lounge featuring entertainment on the weekends. On-site, there’s also a health club with free weights, Nautilus equipment, step and pool aerobics classes, a sauna, and massage services. Off-season midweek rates are about half of what they are in season, and you can ask about holiday and weekend packages.

The hotel was open year-round when I started working there, but as I explained earlier, half of the facilities weren’t completed, which made it quite challenging. But with the help of my friend Eddie, who was in charge of the food and beverage section of the hotel (which was leased out to a Jewish kosher caterer with a great business in Boston), we managed. Eddie was a very nice guy. Unfortunately, the man who owned the hotel never paid us the money he owed our food and beverage corporation, and the poor man almost went broke. That’s when I learned you can’t trust everybody in the world.

This hotel was my first job in the United States, first as a sous chef, and then three weeks later, I replaced the executive chef. So, it was quite stressful for me.

Before I go on to talk about food, I want to mention Gretchen, a girl from Newton who attended Newton College of the Sacred Heart, a Catholic school that was strictly for girls at the time. Whenever I visited, which was only a few times, it felt like I was in the Garden of Eden—all these young girls, and most of them were very good-looking. Like almost all college students during this time, Gretchen worked during the summer holidays to make some extra spending money, and many of them spent the summers on the Cape or in other holiday spots around New England. Some other students came from Ireland.

Gretchen worked in the reservation system for the shows at our hotel. We had a gigantic room that was not only used for functions, but we also had two different shows a night. One was a dinner show, where we had three choices for the main course: lobster, prime rib, or a chicken dish. After that was a cocktail show where we only served cocktails. We had great entertainers, like Sammy Davis Jr., Tina Turner, Ray Charles, The Four Tops, Sonny and Cher, The Four Seasons, Peggy Lee, and tons of great comedians who came down from the Catskills. I’ve lost my notes from a big flood, so I’m sure I’ve forgotten many names.

The first time I saw Gretchen behind the reservation desk, I was in love—or maybe just in lust. I was very scared to ask her for a date, but one night after the dinner show was over and we had served over 1,000 people (which was extremely stressful), I had a few cocktails and told myself, “This is it, now or never.” So, I just went up to the reservation desk and asked her, “Would you like to go out with me sometime?” To my surprise, she said yes. So, we started dating. We didn’t have a car, so our excursions were only close to or around Hyannis, going to a party or club to listen to some music or going to the beach. We had a good time.

But after Labor Day, she had to go back to college, and my time was almost up. Immigration came to see us at the hotel, checked my paperwork, and found many things not completed, but the hotel was very helpful in keeping me employed until the 15th of October. I also had to visit the Judge in Boston for a personal meeting and a long conversation. The Judge was a hobby cook, and we mostly talked about food. On top of that, he had been stationed in Germany. After about two hours, his words, which I will never forget, were, “All right, young man, I will give you an excellent recommendation. Return to Canada, talk to your lawyer, and finish your paperwork. You will be able to come back next year. But you need to know that you need to get a job on the Cape, and your green card will be ready after the season.”

After I left the Cape, I wasn’t sure if Gretchen would wait for me, but she visited me in Montreal twice, so she must have liked me at least a little. We never fought over the years we were together. I still think about her, particularly when I’m writing about my life.

During my early years in the United States, working as a chef in the 70s, 80s, and even early 90s, I would say most restaurants, hotels, and clubs served what was called continental cuisine—a mixture of French and Italian cooking with some local specialties, depending on what part of the United States you were in and who the predominant settlers were. In the Midwest, it was Germans, Bohemians, Poles, and Scandinavians; on the East Coast, it was Italians and Irish. All the big cities had at least a couple of great French or Italian restaurants and definitely a great steakhouse. Many of the well-known chefs were transplants from Europe.

Let me give you some examples of the menus I created during my time. Let’s start with soups. Not all of them were on the menu at the same time, but restaurants typically featured a main soup and a special soup of the day. For example, French onion soup or crab and lobster bisque, New England clam chowder (which needed to be on the menu), a creamy vegetable soup like cauliflower, broccoli, or chicken. Sometimes gazpacho, a chilled soup from Spain, or vichyssoise, a French specialty. In New York, you’d find Manhattan clam chowder; in Louisiana, you always had gumbo with either seafood, chicken, or Cajun sausage.

Salads usually consisted of Caesar salad with croutons and shaved Parmesan, mixed greens with cherry tomatoes, sliced cucumbers, shredded carrots with a choice of dressings, California Cobb salad, a Caprese salad with buffalo mozzarella, sliced tomatoes, balsamic reduction, and basil chiffonade. Iceberg wedge salads were topped with blue cheese dressing and crisp bacon bits.

The appetizers in most hotels included chilled oysters on the half shell with cocktail sauce, littleneck clams, shrimp or lobster cocktail with cocktail sauce, house-made pâté or terrine with Cumberland sauce, smoked salmon garnished with capers and onions, steak tartare, and carpaccio of beef with mustard sauce. Hot appetizers usually included clams casino, oysters Rockefeller, Coquilles St. Jacques, steamed mussels, shrimp scampi with garlic, lemon butter, and herbs, fried calamari with cocktail sauce, crab cakes with corn relish and lemon aioli, and grilled polenta served with tomato coulis topped with Gorgonzola and placed under the salamander.

In New England, lobster is king. There are different kinds of lobster dishes, like baked stuffed lobster, grilled lobster split in half, broiled lobster, and of course, the famous lobster roll. Baked scrod, which is a small cod, is topped with a cracker crust, herbs, white wine, butter, and then baked. Stuffed flounder with lobster stuffing is baked in the oven and topped with Newberg sauce. Seafood Newburg, with lobster, shrimp, scallops, maybe some clams and mussels, is cooked with sherry and served in a lobster sauce. Baked or casseroled scallops, grilled tuna or swordfish topped with garlic butter and served with fresh lemon were also popular. Sometimes we had pasta dishes like spaghetti sautéed with garlic, shrimp, scallops, lobster, mussels, littlenecks, or all of them together for a dish called frutti di mare—fruits of the sea. Grilled salmon steak, baked stuffed shrimp, poached salmon fillets, and linguini alle vongole (littlenecks with pancetta, thinly sliced garlic, herbs, white wine, butter, and grated Parmesan) were other common offerings.

Beef dishes during this time were more straightforward: filet mignon topped with sauce béarnaise, New York strip with green peppercorn sauce, medallions of beef also known as steak au poivre, or Steak Diane. Many restaurants served prime rib, which you could order three different ways: with the bone attached, boneless, or English style with thinner slices. Many people, when they made reservations, asked if we could reserve them an end cut. It was usually served piping hot with freshly grated horseradish, a popover (similar to Yorkshire pudding), baked potatoes with sides of butter, cheddar cheese, sour cream, chives, and bacon. The server would assist you with your preferred toppings, and this was done tableside. The preferred vegetable was often broccoli, simply topped with melted butter, and sometimes with hollandaise sauce. This was one of the most preferred meals in my younger years as a chef. I loved baked potatoes and prime rib. On a good night, you could easily serve four to five whole prime ribs, and in a busy restaurant, it always sold out before the evening was over.

If, for example, you worked in Texas, the Midwest, or the Southwest of the United States, you would find many more beef dishes on the menu, such as Porterhouse and cowboy steaks, ribeye steak, flank steak, and particularly in Texas, smoked BBQ beef ribs and brisket. Some hotels offered these under their banquet menus, but I would suggest going to a good local BBQ joint.

During the 70s, probably the biggest craze when it came to food was steamed Alaskan king crab legs served with a steak, along with corn on the cob, lemon butter, and vegetables. Today, there is no way you can serve this dish—it would be much too expensive. Lamb chops were seldom on the menu, but when they were, they were usually grilled and served with mint jelly. Pork in restaurants during my time as an executive chef was seldom on the menu, but when it was, it was usually sautéed pork tenderloin with a mustard sauce or a mustard and pickle sauce. I featured some of my own dishes on my menus, like stuffed pork chops with sausage, sautéed and served with the many fabulous relishes and chutneys for which New England is famous.

During this time, we also had veal dishes, particularly on the East Coast, although they were not offered every night. We changed them up, with dishes like veal Milanese, veal princess with fresh asparagus spears and hollandaise sauce, veal piccata, scallopini of veal saltimbocca or Marsala. Some chefs added mushrooms to the Marsala sauce. Veal Cordon Bleu was stuffed with cheese and ham. Veal Oscar was always a hit, topped with asparagus, Alaskan king crab legs, and sauce béarnaise. These dishes were usually served with sautéed potatoes or pasta. Some restaurants featured veal chops on the menu, but not too often.

Nowadays, where there is much controversy over how veal is treated, it has gone out of fashion. But I personally love veal, and if it’s good veal, there’s nothing wrong with it. When I visited Germany, all the beef and veal came from young cattle that roamed the fields and were never in cages. But American publicity, sometimes total nonsense, made it sound like these animals were mistreated, but this is America. During this time, many of the veal dishes were substituted with boneless chicken breasts and served with the same toppings if they were still on the menu. These were usually served à la orange or à la bigarade, normally with wild rice.

Desserts during this time were very much American: different pies like blueberry, apple, strawberry rhubarb, pecan, fruit cobblers all served with vanilla ice cream, shortcakes with strawberries marinated and topped with whipped cream, New York cheesecake—you had to have New York cheesecake on the menu—with fresh marinated fruits such as strawberries or blueberries. There was also Boston cream pie, crème brûlée, chocolate mousse, and assorted scoops of ice cream, usually three small scoops like strawberry, vanilla, chocolate, or a mix of ice cream pies.

That was the desserts. So basically, I wanted to tell you about this because most good restaurants served what was basically called French Continental cuisine, and these dishes were served in almost all the hotels. Then slowly but surely, it changed, where chefs added local ingredients and made it much different than what it was during my time as an executive chef in Hyannis. Whether I worked at The Paddock, in Newport, RI, or even in Lakeway, TX, right outside Austin, these were some of the main items you needed on the menu to make people happy.

Traditional New England Clam Chowder

Ingredients:

4 center-cut bacon strips

2 celery ribs, chopped

1 large onion, chopped

1 garlic clove, minced

3 small potatoes, peeled and cubed

1 cup water

1 bottle (8 ounces) clam juice

3 teaspoons reduced-sodium chicken bouillon granules

1/4 teaspoon white pepper

1/4 teaspoon dried thyme

1/3 cup all-purpose flour

2 cups fat-free half-and-half, divided

2 cans (6-1/2 ounces each) chopped clams, undrained

CLAM CHOWDER TIPS

What is New England clam chowder?

New England clam chowder normally contains clams, potatoes, onions, salted pork and milk or cream. The addition of dairy is considered the biggest difference from other chowders. New England clam chowder is a classic American staple, first eaten by settlers as early as the 1700s. Be sure to check out our other wickedly good New England recipes!

What toppings can I add to clam chowder?

Classic clam chowder toppings are oyster crackers, chopped cooked bacon and fresh chives.

How do you thicken clam chowder?

This clam chowder is thickened with a slurry, a mixture of fat-free half-and-half and flour. By mixing these two together, you will prevent clumping. Cook the soup until it has thickened, and the taste of flour will be cooked out. Follow these additional soup thickening tips!

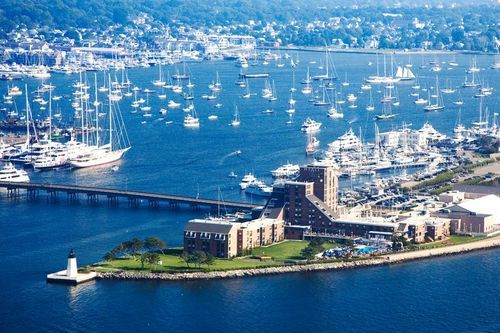

Newport, Rhode Island

Alright, I would now like to talk about something that really sent me in a different direction, which was a hotel in Newport, RI, called the Sheraton Goat Island. I got a call from a German general manager named Klaus Ottmann. He needed an executive chef. At first, I was hesitant. Could I handle the job? But he assured me that he would help me. His background was very similar to mine. He had started as a cook in Germany and worked his way up. He told me, “Gert, I will be by your side from the beginning.” And I can tell you one thing, this is the man who actually shaped me into a good executive chef and taught me how to work, organize myself, and how to treat people.

So I went down to Newport, Rhode Island, for a day, and it was on my day off. I asked Gretchen if she could maybe take a break from school, and she was ready to say, “Yes, I’ll take a break.” So we went down there together. The two years I spent in Newport were wonderful. Gretchen and I visited many more places in New England during this time, and I learned how to be in charge of a real collection of people.

Tom, who worked as a broiler man, originally came from Wisconsin and had played football in college until he got hurt. During high school, he had worked in kitchens, so thank God he had something to fall back on. He was a great worker and a great grill cook. The broiler was an important position at the time because when the steaks were ready, the rest of the food on the ticket had to be ready too. He was the lead guy, and seldom was a steak not cooked to perfection.

Mario, who was my rounds cook, was a Filipino who had joined the Navy like so many of his countrymen. He had served on a nuclear submarine. He told me many stories about his time at sea and how many sailors couldn’t handle the months of being on the water, the closeness, and the feeling of being like a sardine packed in a tin can. Not seeing the sun, no news from the outside world, and the total unknown of what could happen without a moment’s notice. All the torpedoes were tipped with nuclear warheads. This was the Cold War, and the subs were on total alert 24 hours a day. Through him, I met many Filipinos who had started off like him in the military, then got out, brought their families to the United States, and made their dreams a reality. He was hardworking, extremely smart, and driven to become a great chef. He had a great family, and all of his children became doctors or nurses, and a cousin of his became a congressman. We became very close friends, and I am the godfather of his only son. By some coincidence, we lost touch, and I have no idea where he might be now.

The prep crew was a funny bunch, and Mario helped out with them for overtime pay. Danny, also an old Navy man, loved to take a sip from the liquor cabinet. Many mornings, he would say, “Chef, I need a little nip,” his hand shaking. I tried to tell him, “Dan, go to rehab.” “Yes, Chef,” was the answer. “Tomorrow I will go, just a little today, that’s all I need.” Many times, I said to myself, “Gert, what you are doing is wrong, you are enabling him.” Mario always said the same thing, “Chef, don’t worry about him. You know you have a banquet to serve. His liver was gone before you arrived, and it will either survive after you are gone, or he will live for a few more years and then he will die.” Maybe Mario’s harshness came from his childhood—I know they were very poor—or perhaps from the submarine days. He always told me, “Gert, you are too nice. It’s not your obligation to care for your cooks’ lives.”

Our other co-worker was Antoinette, a French woman who had come to America through marriage. What a woman! She could out-prep anyone, always in a great mood, never complaining, and always ready for a little mischief. A great cook, a jewel of a human being, and all she ever asked for was a glass of red wine. I was more than happy to get it for her. I am sure that the purchasing agents set aside a few bottles for her. I told her once, “You can have a bottle if you like.” Her answer? “Absolutely not. The morning prep crew can’t afford another dent!” The team was the best. They worked their asses off, but we also had a lot of fun. I was always thankful to them; their work was crucial to my success. There were others working in the kitchen part-time, high school students, but Tom, Mario, Danny, and Antoinette—they were the real deal.

I will also never, never forget Don, Dan Cutler, the best short-order cook who ever worked for me. He could serve 100 breakfasts all by himself. I had it all—a great crew, a beautiful girlfriend who was loved by everybody.

The hotel was located on Goat Island, a former naval shooting range during the Second World War. The hotel had a separate coffee shop, and we opened for breakfast and lunch, serving regular coffee shop food. This was Dan Cutler’s domain. I never had to worry about him. Another restaurant was the Raw Bar. It seated about 100 people and served oysters, clams, littlenecks, shrimp, and crab claws, and we usually opened only on weekends. It had the normal New England fare, but with my arrival, we added some more specials like veal scaloppini, veal chop, and lamb specials. I worked very hard with some of the local fishermen to get some unusual seafood if they could find it. I became one of the first New Englanders to sell fresh tuna and swordfish. Cod was still the most popular fish in New England restaurants, and we served it constantly. But we could not get enough lobsters. We served them boiled, baked, and stuffed. Sometimes, I created a special like Lobster Américaine or Thermidor, but even they could not replace the lobster casserole topped with lobster sauce. Remember, it was still the 1970s, and we were in New England. It had always been a conservative bastion for food, and it was no different. New England was the last holdout for traditional Americanized continental cooking. The new food revolution that had started in California swept the nation due to many chefs, but especially Julia Child’s TV show, propelling chefs into the 80s and 90s to incorporate local ingredients and reinvent old recipes. We had always done this in Europe, where people would never settle for canned green beans, peas, or carrots.

Another of our great successes was the Sunday brunch. We could serve in the neighborhood of 400 people with a wonderful display of chilled seafood, smoked fish, an array of fresh fruit, an omelette station where they were made to your liking, a roast beef and ham station, eggs Benedict, eggs Florentine, corned beef hash, salted codfish patties, roasted potatoes, bacon, sausage, and chicken crêpes, all beautifully presented in silver chafing dishes. There were also muffins, Danish pastries, and petits fours. It was a great feast and a feast for the eyes. Gretchen loved it, and Klaus always invited her for Sunday brunch, Friday dinners, Saturdays, and any other time she wanted to come. You can imagine, for a poor college student, this was a treat. I wondered, is that why she stayed around?

We were also busy with lots of banquets, weddings, and other parties. The bar was on top of the building and had a beautiful view of Newport and the bay. My apartment was basically a hotel room, but it was a corner unit overlooking the Newport Bridge and the bay. It was more than big enough for me. You could get there from outside without going through the lobby, so I had privacy. Maid service and laundry were handled by a lovely maid who adored me. It was a dream time in my job and a dream time in my life.

Mr. Ottmann was a strict manager, but also very fair. Little did I know when he said he would help me, he would guide me along the path to becoming a competitive executive chef. He introduced me to the Chaîne des Rôtisseurs, a prestigious French society. We hosted their dinners many times with classical French menus consisting of seven courses. It was a lot of fun. During this time, I entered the culinary show in Boston twice and won gold medals both times—one for a cold turkey dish and one for a gigantic 5 lb. lobster. Mr. Ottmann made sure I got my dues and always made sure that the local papers covered it. He was a wonderful mentor, and I will always be grateful to him.

During my time in Newport, RI, I saw a town slowly being rebuilt. During the Roaring 20s, Newport filled up with the ultra-rich. They mingled with some of the old established money who had the “cottages”—which were more like castles and chateaux. They played tennis and sailed the coast. With the crash of 1929, it almost all stopped; most left, but the Navy stayed. When the Second World War broke out, Newport became a Navy town. In the early 1970s, houses were restored, and some other buildings on Main Street got a facelift. Then the America’s Cup got things going again. The Tennis Hall of Fame was reborn, the cottages were put into a trust and restored to their former glory, and the Newport Jazz Festival became a gigantic hit. With all this going on, bars and restaurants opened, and if you go there today, it is overrun by tourists. In my days, it was calmer, and on days off, I would visit the coast, inlets, and bays, marvel at the beauty of nature, and look out at the endless Atlantic, dreaming about the present and the future.

Newport, in the early colonial days, was a center for religious tolerance, thanks to the liberal ideas of Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island. Quakers and Jews joined the Baptists who had followed Williams and made it their home. Their differences and hard work were instrumental in Newport’s success. In the 1960s, the town looked trapped in time, but restoration projects started, and many homes and other buildings were restored. The White Horse Tavern was among them, but it almost didn’t happen because of the two churches on either side. They tried to block it from getting a liquor license, but thanks to the state passing a special law that exempted taverns built before the 1700s, it was saved. The tavern is a beautiful place, and Klaus and I once thought we should take over the lease, and I think Tran Sartorial did at one time too. The town square is typically New England with the green and the beautiful Episcopal church dominating the square.

There are beautiful parks in Newport, most celebrated being an open-sided stone structure. Among the various explanations is that it had Viking origins, that it was the Solstice legacy erected by giants, that pirates stored their bounties there, or that maybe it was just the wind. So the sagas abound, and as time goes on, no doubt people will come up with others.

I visited the Newport Casino, which was built at the height of the American Renaissance period. Lawn tennis was its pinnacle, and Newport hosted the National Tennis Championship from 1881 to 1914, which later became the US Open. No one visits Newport without walking the mansion walk of great homes, which were modeled after French châteaux, English country houses, and Italian palazzos. The “cottages” were summer homes for the fabulously rich, primarily from New York, and are located on Bellevue Avenue and Ocean Drive. The Elms, a French Renaissance château, the Château-sur-Mer, are beautiful, but the most famous of them all is The Breakers, built for Cornelius Vanderbilt, who was at the time the richest man in the country, known for his enormous ego and vanity. He used it only 10 weeks out of the year. It took 2,500 workers two years to complete, with materials constructed in Europe and shipped to Newport. You might recognize the Rosecliff, where The Great Gatsby was filmed, or you can go see the beach mansion, the Marble House, the summer home of the Astors. It goes on and on—Belcourt Castle is modeled after Louis XIV’s hunting lodge and has more than 60 rooms filled with European treasures, among them 13th-century stained glass windows and a 13,000-piece crystal chandelier from Imperial Russia. There are many others, and now Newport’s famous legacies and attractions are well known. The city is also known for the America’s Cup Museum and the summer home of the New York Yacht Club, where hundreds of regattas are held each summer.

In 1803, Newport had gas lights installed. They claim a Newport man ate the first tomato, but this cannot be true since tomatoes were being eaten in Europe in the 17th century, although they were long thought to be poisonous. There was also a synagogue in Newport, which was America’s first in 1763, and in 1657, they had the first free public schools in 1640. So, Newport has a lot to offer. Gretchen and I loved Newport, and we spent a good part of our time together in the city. She usually came down on Fridays, Monday was my day off, so we left after brunch on Sunday and went to Boston. While I worked late on Saturdays, she studied or sunbathed outside my apartment. East Coast people loved the sun and didn’t seem to be afraid of skin cancer or wrinkles in old age. Many Portuguese settled in New England, particularly in the New Bedford and Fall River areas of Massachusetts. These vibrant areas still had many immigrants who never learned to speak English. Some of the local restaurants reminded me of Porto with their awesome kale soup and salted cod. We frequently stopped there on our way to Boston for good and plentiful portions. Gretchen, being in college, and me, in my first job as an executive chef, didn’t have much time for long vacations, so we made the most of our days.

There will be many, many more stories I will write about the New England area, and I think I might want to put together a book entirely about New England. Well, all this beauty has to end, as they say, all good things must come to an end. Klaus Ottmann was the best gentleman I ever worked for, and one morning, I got a call from his secretary to come to the office. This was not unusual. I put on a clean chef’s jacket and told Antoinette that I had to see Mr. Ottmann. I was in a good mood. Then, after telling me to sit down, he said he was going to leave his post and go to Texas. I was stunned, speechless, and could not believe it. “Texas? What are you going there for? It’s nothing but desert, mesquite trees, and tumbleweeds,” I exclaimed. I tried to explain to him and pleaded with him not to go. He must have thought, “What’s wrong with this kid?” Maybe it was my insecurity, maybe it was the feeling of being deserted by a man I admired more than anybody. I felt my world was collapsing. I said something like, “If this is what you want to do, I have to take the rest of the day off to think.” It was Monday, and the hotel was almost empty. I went to my room and felt sorry for myself, but as you will see, everything turned out fine, and soon after, I joined him in Lakeway, outside Austin, TX.

Creamy, soft, and slightly sweet, scallops remain one of our favorite seafoods to cook and eat.

Scallop (/ˈskɒləp, ˈskæləp/)[a] is a common name that is primarily applied to any one of numerous species of saltwater clams or marine bivalve mollusks in the taxonomic family Pectinidae, the scallops. However, the common name “scallop” is also sometimes applied to species in other closely related families within the superfamily Pectinoidea, which also includes the thorny oysters.

Scallops are a cosmopolitan family of bivalves which are found in all of the world’s oceans, although never in fresh water. They are one of very few groups of bivalves to be primarily “free-living”, with many species capable of rapidly swimming short distances and even of migrating some distance across the ocean floor. A small minority of scallop species live cemented to rocky substrates as adults, while others attach themselves to stationary or rooted objects such as sea grass at some point in their lives by means of a filament they secrete called a byssal thread. The majority of species, however, live recumbent on sandy substrates, and when they sense the presence of a predator such as a starfish, they may attempt to escape by swimming swiftly but erratically through the water using jet propulsion created by repeatedly clapping their shells together. Scallops have a well-developed nervous system, and unlike most other bivalves all scallops have a ring of numerous simple eyes situated around the edge of their mantles.

Many species of scallops are highly prized as a food source, and some are farmed as aquaculture. The word “scallop” is also applied to the meat of these bivalves, the adductor muscle, that is sold as seafood. The brightly coloured, symmetric, fan-shaped shells of scallops with their radiating and often fluted ornamentation are valued by shell collectors, and have been used since ancient times as motifs in art, architecture, and design.

Owing to their widespread distribution, scallop shells are a common sight on beaches and are often brightly coloured, making them a popular object to collect among beachcombers and vacationers.[2] The shells also have a significant place in popular culture, including symbolism.

Seared Sea Scallops with a Vibrant Chimichurri Sauce: A Gourmet Delight

Introduction:

Prepare to elevate your culinary repertoire with this gourmet dish that harmonizes the delicate sweetness of perfectly seared sea scallops with the zesty, herbaceous notes of a vibrant chimichurri sauce. This recipe is a celebration of textures and flavors, where the tender scallops meet a fresh, piquant sauce that brings the dish to life. Ideal for impressing guests or indulging in a special dinner, this dish combines simplicity with sophistication, offering a taste experience that’s both comforting and refined.

Ingredients:

1 lb Large Sea Scallops: Look for dry-packed, fresh sea scallops, preferably diver-caught for the highest quality. Avoid wet-packed scallops as they have been treated with phosphates and will not sear as well.

1/2 cup Water with Salt: Use filtered water mixed with 1/2 teaspoon fine sea salt, ensuring a pure and clean brine to enhance the dish’s flavors.

2 Tbsp Red Wine Vinegar: Opt for a high-quality red wine vinegar, such as one aged in oak barrels, to add depth and complexity to the chimichurri sauce.

1 cup Fresh Parsley, Chopped: Use flat-leaf Italian parsley for its robust flavor and vibrant green color. Make sure to chop it finely to release its full aroma.

2 Cloves Garlic, Minced: Fresh garlic is essential. Mince it finely to evenly distribute its pungent flavor throughout the sauce.

Pinch Red Pepper Flakes: Adjust the quantity to your taste, but a pinch is typically enough to add a subtle heat that complements the other ingredients without overpowering them.

3 Tbsp Extra Virgin Olive Oil: Use the best extra virgin olive oil you can find, preferably cold-pressed and unfiltered, to enhance the richness and flavor of both the sauce and the seared scallops.

Freshly Ground Black Pepper to Taste: Opt for freshly ground black peppercorns, which offer a more complex and aromatic flavor compared to pre-ground varieties.

Directions:

Prepare the Chimichurri Sauce:

- Begin by preparing a quick brine. In a small bowl, combine the filtered water and fine sea salt. Microwave for 30 seconds or until the salt has fully dissolved. Stir to ensure a homogenous mixture.

- Once the brine has cooled slightly, whisk in the red wine vinegar, finely chopped parsley, minced garlic, and a pinch of red pepper flakes. These ingredients should be well combined to create a base for the chimichurri.

- Slowly drizzle in 2 tablespoons of the extra virgin olive oil while continuously whisking. This will help emulsify the sauce, ensuring a smooth, cohesive texture. For best results, allow the chimichurri to rest at room temperature for at least 20 minutes to let the flavors meld together. You can also prepare this in advance and store it in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to 3 days, allowing the flavors to deepen further.

Prepare the Scallops:

- Carefully pat the sea scallops dry with paper towels to remove any excess moisture. This step is crucial for achieving a proper sear. Season the scallops generously on both sides with fine sea salt and freshly ground black pepper.

- In a large skillet, preferably cast iron for its even heat distribution, heat the remaining tablespoon of extra virgin olive oil over medium-high heat. Wait until the oil is shimmering and just beginning to smoke, which indicates it’s hot enough for searing.

Sear the Scallops:

- Add the seasoned scallops to the hot skillet, making sure not to overcrowd the pan. Leave enough space between each scallop to prevent steaming. Allow the scallops to cook undisturbed for 2 to 3 minutes on the first side. You’ll know they’re ready to flip when a deep golden-brown crust has formed.

- Using tongs, carefully flip each scallop. Cook for an additional 1 to 2 minutes, or until the scallops are firm to the touch but still slightly yielding in the center. The interior should be opaque and just cooked through. Be careful not to overcook the scallops as they can become rubbery.

Plating and Serving:

- For an elegant presentation, arrange the seared scallops on a warm plate. Drizzle them generously with the vibrant chimichurri sauce, allowing some of the sauce to pool around the scallops for visual appeal.

- Garnish with a few sprigs of fresh parsley or microgreens for a touch of color and freshness. Serve immediately, accompanied by a crisp white wine like Sauvignon Blanc or a light Pinot Grigio, which pairs beautifully with the dish’s bright, herbaceous flavors.

Cultural and Historical Context:

Chimichurri, a sauce that originated in Argentina, is traditionally used as a condiment for grilled meats, reflecting the country’s rich barbecue culture known as “asado.” This version of chimichurri complements the natural sweetness of sea scallops, offering a modern twist on a classic sauce. The dish represents a fusion of coastal seafood cuisine with the robust flavors of South American grilling traditions, making it a delightful expression of culinary cross-pollination.

This recipe is designed to impress, offering both the home cook and the seasoned chef an opportunity to explore a dish that balances simplicity with gourmet finesse. Enjoy the interplay of flavors and textures that make this dish a standout on any table.

Flambéed Whisky Scallops in Creamy Dill Sauce: A Sophisticated Coastal Delight

Introduction:

Indulge in a dish that effortlessly marries the succulent sweetness of fresh scallops with the luxurious richness of cream and the bold warmth of whisky. This recipe, infused with aromatic garlic and fresh dill, creates a symphony of flavors that is both elegant and comforting. The delicate balance between the tender scallops and the silky, whisky-infused sauce makes this dish a true gourmet experience, perfect for a special dinner or an intimate gathering.

Ingredients:

1 Tbsp Vegetable Oil: Use a neutral oil like canola or grapeseed for its high smoke point, which is essential for achieving a quick, golden sear on the scallops.

600 g Fresh Scallops with Roe Attached: Opt for large, fresh scallops sourced from a reputable fishmonger. The roe adds a richer flavor and vibrant color to the dish. If possible, choose diver-caught or day-boat scallops for their superior quality and sustainability.

1 Cup Heavy Cream: Use full-fat heavy cream to achieve the desired richness and smooth texture. Look for organic or locally sourced cream for the best flavor.

2 Garlic Cloves, Minced: Fresh, finely minced garlic is key to imparting a deep, aromatic base to the sauce.

Salt & Freshly Ground Pepper, to Taste: Season with fine sea salt and freshly ground black pepper for the most balanced and aromatic seasoning.

½ Cup High-Quality Whisky: Choose a whisky with a smooth, balanced flavor profile—preferably one with notes of vanilla, caramel, and oak, which will complement the creaminess of the sauce. Avoid using overly peaty or smoky whiskies, as they can overpower the delicate scallops.

¼ Cup Fresh Dill, Chopped: Fresh dill adds a bright, herbaceous note that beautifully contrasts with the richness of the cream and the warmth of the whisky. Make sure to chop it finely to release its full flavor.

Optional: Sliced Potatoes or Fresh Tagliatelle: Serve the scallops over a bed of thinly sliced, sautéed potatoes or freshly cooked tagliatelle for a complete and satisfying meal.

Directions:

Prepare the Pan:

- Select a deep, heavy-based pan or skillet, preferably cast iron or stainless steel, for even heat distribution. Heat the vegetable oil over high heat until it shimmers and is just about to smoke. This ensures the pan is hot enough to sear the scallops properly, creating a crisp, golden crust.

Sear the Scallops:

- Pat the scallops dry with paper towels to remove any excess moisture. This step is crucial for achieving a proper sear. Season the scallops lightly with salt and freshly ground black pepper just before cooking.

- Place the scallops in the hot pan, making sure not to overcrowd them. Fry the scallops quickly on each side, about 30 seconds per side, until they develop a golden-brown crust. Avoid moving the scallops around in the pan to ensure even browning. The roe should remain intact, adding both flavor and visual appeal.

Prepare the Sauce:

- Once the scallops are seared, reduce the heat to medium and add the minced garlic to the pan. Sauté the garlic for about 30 seconds, just until fragrant, being careful not to let it burn.

- Pour in the heavy cream, stirring gently to combine with the garlic and any caramelized bits left from the scallops. Bring the mixture to a gentle simmer, allowing it to thicken slightly. This will create a rich, velvety sauce that clings beautifully to the scallops.

Flambé with Whisky:

- Carefully add the whisky to the pan. To flambé, tilt the pan slightly to allow the whisky to catch the flame from the burner, or use a long lighter to ignite the alcohol. This will burn off the alcohol, leaving behind the deep, complex flavors of the whisky. Allow the flame to subside naturally, then stir the sauce to ensure it’s well mixed.

Finish with Fresh Dill:

- Once the whisky has flambéed, stir in the freshly chopped dill. This adds a fresh, herbal brightness that cuts through the richness of the sauce. Taste the sauce and adjust seasoning with salt and pepper as needed.

Plating and Serving:

- For an elegant presentation, arrange the seared scallops over a bed of thinly sliced, sautéed potatoes or freshly cooked tagliatelle. Spoon the creamy dill sauce generously over the scallops, ensuring each serving is well coated.

- Garnish with additional fresh dill sprigs or a sprinkle of finely chopped dill for a pop of color. Serve immediately, paired with a crisp white wine such as Chardonnay or a light Sauvignon Blanc to complement the dish’s rich, creamy flavors.

Cultural and Historical Context:

This dish is a refined take on traditional coastal cuisine, where fresh seafood is often paired with rich, creamy sauces. The use of whisky adds a unique twist, bringing warmth and depth to the dish, while the flambé technique enhances both the flavor and the dining experience. The inclusion of fresh dill, a common herb in Scandinavian and Eastern European cuisines, ties the dish to a broader culinary tradition, making it a delightful fusion of flavors and techniques.

This recipe offers an opportunity to explore the interplay of bold, rich flavors and delicate, tender textures. The dramatic flair of flambéing the whisky not only intensifies the dish’s aroma but also creates a memorable cooking experience that will surely impress any guest. Enjoy this sophisticated dish as a centerpiece for your next special occasion.

Kathie Lee Gifford

Caviar (also known as caviare; from Persian: خاویار, romanized: khâvyâr, lit. ’egg-bearing’) is a food consisting of salt-cured roe of the family Acipenseridae. Caviar is considered a delicacy and is eaten as a garnish or a spread.Traditionally, the term caviar refers only to roe from wild sturgeon in the Caspian Sea and Black Sea (Beluga, Ossetra and Sevruga caviars). Depending on the country, caviar may also be used to describe the roe of other species of sturgeon or other fish such as salmon, steelhead, trout, lumpfish, whitefish,or carp.

The roe can be “fresh” (non-pasteurized) or pasteurized, with pasteurization reducing its culinary and economic value.

“If you eat caviar every day it’s difficult to return to sausages”.

Arsene Wenger

Classic Russian Blini: Delicate Pancakes with a Gourmet Twist

Introduction:

Blini, the delicate Russian pancakes, are a timeless culinary delight that can be dressed up or down to suit any occasion. These tender, pillowy pancakes are perfect for both sweet and savory pairings, making them a versatile addition to your gourmet repertoire. In this recipe, you’ll learn how to create perfectly golden blini with a rich, buttery flavor. Whether served with caviar and crème fraîche or a sweet dollop of jam, these blini are sure to impress.

Ingredients:

1 Cup All-Purpose Flour: Use a high-quality, unbleached all-purpose flour for the best texture. For a more authentic, traditional flavor, consider substituting 1/3 cup of the all-purpose flour with buckwheat flour, which gives the blini a nuttier taste and a slightly denser texture.

¾ Teaspoon Fine Sea Salt: Fine sea salt is ideal as it dissolves more evenly into the batter, providing a consistent flavor throughout.

½ Teaspoon Baking Powder: Baking powder is essential for giving the blini a light, fluffy texture. Ensure your baking powder is fresh for optimal rising.

¾ Cup + 2 Tablespoons Whole Milk: Whole milk provides the necessary fat content for a rich batter. If possible, use organic or locally sourced milk for the best flavor.

1 Large Egg: The egg adds structure and richness to the blini. Ensure it is at room temperature to help the batter mix smoothly.

1 Tablespoon Unsalted Butter, Melted: Unsalted butter is preferred to control the salt content in the recipe. Melt the butter and allow it to cool slightly before mixing it into the batter.

1 Additional Tablespoon Unsalted Butter for Cooking: Use high-quality unsalted butter for cooking the blini. The butter not only adds flavor but also helps achieve a beautifully browned surface.

Directions:

Prepare the Batter:

- In a medium mixing bowl, sift together the all-purpose flour (and buckwheat flour, if using), fine sea salt, and baking powder. Sifting ensures that the dry ingredients are well combined and free of lumps, leading to a smoother batter.

- In a separate bowl, whisk together the whole milk, room-temperature egg, and the melted, slightly cooled butter. Whisk until the mixture is fully combined and slightly frothy.

- Gradually pour the wet ingredients into the dry ingredients, whisking gently to combine. Be careful not to overmix the batter—stir just until the ingredients are incorporated to avoid tough blini. The batter should be thick yet pourable, similar to a pancake batter.

Rest the Batter:

- Let the batter rest at room temperature for about 10-15 minutes. This allows the flour to fully hydrate and the baking powder to activate, resulting in lighter, fluffier blini.

Cook the Blini:

- Heat a non-stick skillet or a well-seasoned cast-iron pan over medium-low heat. Add 1 tablespoon of unsalted butter, swirling the pan to coat the bottom evenly.

- Using a tablespoon measure, drop small dollops of batter into the skillet, spacing them out to allow for spreading. Each blini should be about 2 inches in diameter, perfect for individual servings.

- Cook the blini until bubbles start to form on the surface and the edges begin to set, approximately 1 1/2 to 2 minutes. Carefully flip the blini using a thin spatula, and cook for an additional minute or until the other side is golden brown.

- Transfer the cooked blini to a plate lined with a paper towel to absorb any excess butter. Repeat the process with the remaining batter, adding more butter to the skillet as needed to prevent sticking and ensure a rich, buttery flavor.

Plating and Serving:

- Serve the blini warm, arranged on a platter for an elegant presentation. For a gourmet experience, pair the blini with traditional accompaniments such as smoked salmon, caviar, crème fraîche, and fresh dill. Alternatively, for a sweet variation, serve with a selection of fruit preserves, whipped cream, or a drizzle of honey.

- Garnish with fresh herbs or edible flowers for an added touch of sophistication. Blini can be served as an appetizer, a light brunch, or even as a canapé at a cocktail party.

Cultural and Historical Context:

Blini are a staple in Russian cuisine, traditionally served during Maslenitsa, the Russian festival celebrating the end of winter and the arrival of spring. These small, thin pancakes symbolize the sun and are enjoyed in various forms across Eastern Europe. By incorporating buckwheat flour, you connect with a more traditional version of blini, often enjoyed in rural Russian households.

This blini recipe offers a gateway to exploring the rich culinary traditions of Eastern Europe, with a modern gourmet twist. Whether served savory or sweet, these versatile pancakes are sure to become a favorite in your recipe collection, perfect for any occasion that calls for something special.

Serving Caviar in the Manner of the Russian Imperial Tsars: A Journey into Opulence and Tradition

Introduction: The Glimmering Jewel of Russian Imperial Cuisine

Caviar, the luxurious delicacy harvested from the roe of sturgeon, holds a place of honor in the pantheon of Russian Imperial cuisine. During the era of the great Russian tsars, caviar was more than just a food—it was a symbol of wealth, power, and the refined tastes of the aristocracy. The rituals surrounding caviar service were steeped in tradition, reflecting the opulence of the Russian court and the grandiosity of its feasts. To serve caviar in the manner of the tsars is to step back in time to a world where every detail was meticulously orchestrated to display the might and majesty of the Russian Empire. This article delves into the history, etiquette, and techniques of serving caviar in the style of the Russian Imperial court, offering a glimpse into the sumptuous lifestyle of the tsars and their retinues.

The Caviar of the Tsars: Sourcing and Selection

During the height of the Russian Empire, caviar was sourced primarily from the Caspian and Black Seas, home to the most prized species of sturgeon: beluga, osetra, and sevruga. These varieties were favored by the tsars for their distinctive flavors and textures:

Beluga Caviar: The most coveted and expensive of all caviar, beluga eggs are large, soft, and pale gray, with a delicate, buttery flavor that melts on the tongue. This was the preferred caviar of the Russian aristocracy, often reserved for the most prestigious occasions.

Osetra Caviar: Slightly smaller and firmer than beluga, osetra caviar varies in color from golden to dark brown and has a rich, nutty flavor with a hint of sea breeze. Its complex taste made it a favorite among connoisseurs at the Imperial court.

Sevruga Caviar: The smallest and most abundant of the three, sevruga caviar is dark gray and has a more pronounced, briny flavor. While less expensive, it was still highly prized and often served in larger quantities during lavish feasts.

Caviar was carefully harvested by trained fishermen, known as “caviar masters,” who were skilled in the art of extracting and preserving the delicate eggs. These masters ensured that only the highest quality caviar reached the tables of the tsars, often using traditional methods that had been passed down through generations.

The Ritual of Serving Caviar: Tools, Preparation, and Presentation

Serving caviar in the Russian Imperial court was an elaborate affair, governed by strict etiquette and an array of specialized tools. Here is a step-by-step guide to replicating this experience:

1. Preparing the Caviar

Temperature: Caviar was always served chilled, never frozen. The ideal temperature for serving is between 26-32°F (-3 to 0°C), which preserves the delicate texture and enhances the flavor. In the Imperial court, caviar was often stored in special ice-filled containers crafted from crystal or silver.

Serving Vessels: Caviar was traditionally presented in ornate containers made of crystal, gold, or silver, often placed atop a bed of crushed ice to maintain the perfect temperature. It was essential that the vessels were non-reactive, as metal could impart an undesirable taste to the caviar.

2. The Tools of the Trade

Mother-of-Pearl Spoons: The use of metal spoons was strictly forbidden, as they could taint the flavor of the caviar. Instead, mother-of-pearl spoons were employed, their smooth, non-reactive surface ensuring the purity of the taste. Occasionally, utensils made from bone, horn, or even gold were used.

Blini and Toast Points: Accompaniments such as blini (small, tender pancakes) and toast points were customary, offering a neutral base that allowed the caviar’s flavor to shine. These were often served warm, enhancing the overall sensory experience.

Garnishes: The tsars preferred minimal garnishes, allowing the caviar to take center stage. However, traditional accompaniments might include finely chopped egg whites and yolks, crème fraîche, and finely diced shallots, all served separately so guests could tailor their bites to their liking.

3. The Ceremony of Service

Role of the Servants: In the Russian Imperial court, caviar service was often performed by the court’s most trusted servants, who were trained in the precise etiquette of the ceremony. The caviar would be presented to the tsar and his guests with great reverence, often accompanied by a flourish of trumpets or other musical fanfare.

Serving Etiquette: Caviar was typically served as the first course of a grand feast, setting the tone for the opulence to follow. Guests would be offered a small portion on a mother-of-pearl spoon, allowing them to savor the delicacy’s subtle complexities. It was considered a grave faux pas to overindulge in caviar, as restraint was seen as a sign of sophistication.

Pairing with Beverages: Vodka was the preferred accompaniment to caviar, served ice-cold in crystal shot glasses. The crisp, clean taste of vodka was believed to cleanse the palate, allowing the full flavor of the caviar to be appreciated. Alternatively, champagne was also a popular pairing, its effervescence providing a delightful contrast to the rich, creamy texture of the caviar.

Historical Anecdotes: Caviar and the Grandeur of the Russian Court

Caviar was not just a delicacy but a status symbol in the Russian Imperial court, and its service was often accompanied by displays of grandeur. One such tale involves Tsar Alexander II, who was known for his lavish feasts that often featured copious amounts of caviar. It is said that during a state banquet, the Tsar once ordered a caviar-filled Fabergé egg to be presented to each of his guests, a gesture that epitomized the excesses of the Russian aristocracy.

Another notable figure, Catherine the Great, was a renowned lover of caviar. Her court famously served caviar not only at grand banquets but also as an everyday indulgence. Her passion for the delicacy was so great that she is said to have received regular shipments of fresh caviar from the Volga River, ensuring that her table was never without this prized treat.

Recreating the Experience Today: A Modern Adaptation

While few can replicate the exact splendor of a Russian Imperial feast, it is possible to recreate the experience of serving caviar in a manner befitting the tsars in a modern setting:

Sourcing Caviar: Today, sustainable caviar farming has made high-quality caviar more accessible. Look for reputable sources that offer beluga, osetra, and sevruga caviar, ensuring they are sustainably harvested and of the highest quality.

Setting the Scene: To evoke the ambiance of the Russian court, consider using fine china, crystal glassware, and silver utensils in your presentation. Dim the lights and play classical Russian music to enhance the atmosphere.

Elevating the Service: While traditional accompaniments like blini and toast points are always appropriate, consider offering modern twists such as truffle butter, avocado slices, or even a touch of edible gold leaf to add a contemporary flair to the experience.

Pairing with Vodka and Champagne: Just as in the Russian court, pair your caviar with ice-cold vodka or a bottle of fine champagne. For a unique twist, consider serving a vodka tasting with various infusions that complement the caviar’s flavor profile.

Conclusion: A Taste of Imperial Russia

Serving caviar in the manner of the Russian tsars is not just about enjoying a delicacy; it’s about embracing a rich cultural heritage that speaks to the opulence and grandeur of a bygone era. By following the traditions, techniques, and etiquette of the Russian Imperial court, you can create an unforgettable dining experience that honors the legacy of the tsars while delighting the senses of your guests.

A Culinary Treasure Through History, From Ocean Depths to Three Michelin Star Kitchens

Introduction: The Historical and Cultural Significance of Shrimp in Global Cuisine

Shrimp, one of the most beloved seafood delicacies, has played a significant role in global cuisine for centuries. From the bustling fish markets of ancient China to the opulent feasts of European nobility, shrimp has been cherished not only for its sweet, delicate flavor but also for its versatility in culinary applications. The history of shrimp consumption can be traced back to prehistoric times, with archaeological evidence suggesting that ancient civilizations along the coastlines of Africa and the Mediterranean harvested shrimp as a key source of protein.

In the modern culinary world, shrimp holds a place of honor, especially in haute cuisine. Chefs in three Michelin star kitchens around the world have elevated shrimp to new heights, experimenting with innovative techniques and presentations that showcase its unique qualities. However, beyond its gastronomic appeal, shrimp is also deeply intertwined with cultural traditions and rituals, making it a true global treasure.

Understanding the Species: A Deep Dive into Shrimp Varieties and Their Habitats

Shrimp is not a monolithic entity but rather encompasses a diverse range of species, each with its own distinct characteristics, habitats, and culinary uses. The most commonly known types include:

Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei): Predominantly farmed in tropical and subtropical regions, this species is prized for its sweet flavor and tender texture. Pacific White Shrimp are widely used in various culinary applications due to their versatility and relatively mild taste.

Tiger Prawns (Penaeus monodon): Known for their large size and bold, slightly briny flavor, Tiger Prawns are often found in the warm waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. They are a favorite in grilling and broiling, where their robust texture can stand up to intense cooking methods.

Northern Prawn (Pandalus borealis): This cold-water species, commonly found in the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, has a firm texture and a distinctly sweet flavor. Northern Prawns are often used in Scandinavian dishes, such as smørrebrød (open-faced sandwiches) and seafood salads.

Brown Shrimp (Farfantepenaeus aztecus): Native to the Gulf of Mexico, Brown Shrimp have a firmer texture and a more pronounced, earthy flavor compared to other varieties. They are commonly used in dishes like gumbo and jambalaya in Southern American cuisine.

Spot Prawns (Pandalus platyceros): Although called prawns, Spot Prawns are technically a type of shrimp. They are highly prized for their sweet, delicate flavor and are often served in high-end restaurants, particularly on the West Coast of the United States and Canada.

Sustainable Fishing Practices

Sustainability is a critical concern in the modern seafood industry, particularly with regard to shrimp fishing. Overfishing and environmentally damaging practices, such as bottom trawling, have led to significant declines in shrimp populations and the degradation of marine habitats. To combat this, sustainable fishing methods, such as trap fishing and aquaculture with strict environmental controls, have been developed. These practices ensure that shrimp populations remain healthy and that their habitats are preserved for future generations.

Consumers and chefs alike are encouraged to source shrimp from reputable suppliers who adhere to sustainable practices. The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) are two organizations that certify seafood as sustainable, offering a reliable way to identify environmentally responsible products.

Culinary Techniques: Elevating Shrimp in the Kitchen

As a three Michelin star chef, understanding the nuances of shrimp preparation is essential to creating dishes that delight and surprise. Shrimp’s mild and sweet flavor profile makes it incredibly versatile, allowing it to be paired with a wide range of ingredients and cooked using various techniques.

1. Traditional Methods

Grilling: Grilling shrimp is a time-honored method that imparts a smoky flavor and a satisfying char to the exterior while keeping the interior tender and juicy. For the best results, marinate the shrimp in a mixture of olive oil, garlic, lemon juice, and herbs before grilling. Use skewers to prevent the shrimp from falling through the grates, and grill over medium-high heat for 2-3 minutes per side.

Poaching: Poaching is a gentle cooking method that preserves the delicate texture of shrimp. In a three Michelin star kitchen, shrimp are often poached in a court-bouillon—a flavored broth made with white wine, herbs, and aromatics. This method infuses the shrimp with subtle flavors while maintaining their natural sweetness. Poach the shrimp just until they turn opaque, then immediately transfer them to an ice bath to stop the cooking process.

Sautéing: Sautéing shrimp in butter or olive oil is a quick and efficient way to prepare them, especially when making dishes like shrimp scampi or shrimp risotto. To achieve a perfect sauté, ensure that the shrimp are patted dry before cooking to prevent steaming. Sauté over medium-high heat, allowing the shrimp to develop a slight caramelization on the surface.

2. Innovative Techniques

Sous Vide: Sous vide is a method that involves cooking shrimp at a precise, low temperature in a vacuum-sealed bag. This technique allows for unparalleled control over the texture and doneness of the shrimp. To sous vide shrimp, season them with salt, pepper, and aromatics, then vacuum-seal and cook at 135°F (57°C) for 15-30 minutes. The result is perfectly cooked shrimp with a tender, buttery texture.

Molecular Gastronomy: In the realm of molecular gastronomy, shrimp can be transformed into unexpected textures and forms. One innovative approach is to create shrimp espuma (foam) using a siphon, which can be used as a delicate topping for seafood dishes. Another technique involves creating shrimp “pearls” using spherification, a process that encases shrimp puree in a thin gel membrane, offering a burst of flavor in every bite.

Fermentation: Fermentation is an ancient technique that has found new life in modern gastronomy. Shrimp paste, a fermented condiment made from ground shrimp, is a staple in many Southeast Asian cuisines. In a Michelin star kitchen, this technique can be adapted to create unique condiments or to add umami depth to dishes. Fermenting shrimp with salt and spices for several days allows the flavors to develop and intensify, creating a complex and rich taste.

Preservation and Storage: Maintaining Quality and Flavor

To ensure the best quality, shrimp should be handled with care from the moment they are caught to the time they are served. Proper preservation and storage are crucial to maintaining the shrimp’s delicate flavor and texture.

1. Fresh Shrimp

Storage: Fresh shrimp should be stored at a temperature of 32°F (0°C) to maintain their freshness. If you plan to use the shrimp within 24 hours, store them in a colander set over a bowl, covered with ice and a damp cloth. The ice will melt, allowing the cold water to drain into the bowl below, keeping the shrimp cold and moist.

Cleaning: Before cooking, fresh shrimp should be deveined and cleaned. To do this, make a shallow incision along the back of the shrimp and remove the dark vein using the tip of a knife. Rinse the shrimp under cold water to remove any remaining impurities.

2. Frozen Shrimp

Thawing: Frozen shrimp should be thawed gradually to preserve their texture. The best method is to place the shrimp in the refrigerator overnight. For a quicker thaw, place the shrimp in a sealed plastic bag and submerge them in cold water, changing the water every 30 minutes until thawed.

Freezing: To freeze shrimp, first, rinse and dry them thoroughly. Arrange the shrimp in a single layer on a baking sheet and place them in the freezer until frozen solid. Once frozen, transfer the shrimp to an airtight container or vacuum-sealed bag to prevent freezer burn. Properly frozen shrimp can be stored for up to six months.

Nutritional Benefits: A Healthy Addition to Your Diet

Shrimp is not only a culinary delicacy but also a nutritional powerhouse. It is low in calories and high in protein, making it an excellent choice for those seeking a lean source of protein. A 3-ounce serving of shrimp contains approximately 20 grams of protein and only 84 calories.

1. Rich in Essential Nutrients

Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Shrimp is a good source of omega-3 fatty acids, which are essential for heart health. Omega-3s help reduce inflammation, lower blood pressure, and decrease the risk of heart disease.

Vitamins and Minerals: Shrimp is rich in essential vitamins and minerals, including vitamin B12, iron, and zinc. Vitamin B12 supports brain function and energy production, while iron is crucial for oxygen transport in the blood. Zinc plays a vital role in immune function and wound healing.

Antioxidants: Shrimp contains astaxanthin, a powerful antioxidant that gives shrimp their pink color. Astaxanthin has been shown to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, potentially reducing the risk of chronic diseases.

2. Low in Mercury

Unlike some other seafood, shrimp is low in mercury, making it a safe option for regular consumption. This is particularly important for pregnant women, who are advised to limit their intake of high-mercury seafood.

Conclusion: The Global Legacy of Shrimp

Shrimp has been an integral part of global cuisine for millennia, cherished by cultures from every corner of the world. Whether served in a simple cocktail, grilled to perfection, or transformed through innovative culinary techniques, shrimp continues to captivate the palates of gourmands and casual diners alike.

As we look to the future, the importance of sustainable practices in shrimp fishing and farming cannot be overstated. By choosing responsibly sourced shrimp, we can ensure that this beloved delicacy remains a part of our culinary heritage for generations to come.

In the hands of a skilled chef, shrimp is more than just an ingredient; it is a canvas for creativity, a testament to the ocean’s bounty, and a link to the rich tapestry of culinary history. Whether you are a seasoned chef or a home cook, understanding the intricacies of shrimp preparation and appreciation will undoubtedly elevate your culinary endeavors.

A Global Journey Through the Eight Most Beloved Shrimp Recipes

Introduction: Shrimp – A Global Culinary Gem

Shrimp, with its delicate flavor and versatile nature, has captured the hearts of food lovers around the world. From the bustling markets of Southeast Asia to the fine dining restaurants of Europe, shrimp has become a staple in countless dishes, each reflecting the unique culinary traditions of its region. In this article, we embark on a culinary journey to explore eight of the most beloved shrimp recipes from across the globe. Each recipe is steeped in history, rich in flavor, and brings a taste of its homeland to your kitchen.

1. Shrimp Scampi (Italy)

History and Cultural Significance

Shrimp Scampi is a classic Italian-American dish that has become a staple in households and restaurants alike. While “scampi” traditionally refers to a type of small lobster found in the Mediterranean, Italian immigrants in America adapted the recipe using shrimp, resulting in the dish we know and love today. It is a dish that celebrates simplicity, allowing the natural flavors of the shrimp to shine through with just a few key ingredients.

Ingredients

- 1 lb large shrimp, peeled and deveined

- 4 cloves garlic, minced