Bad Mergentheim's

Medieval Beginnings:

In the tapestry of European history, few threads are as richly colored as that of Bad Mergentheim, a gem nestled in the heart of Germany. Its tale begins in the year 1058, a time when the world was markedly different, yet the foundations of modern Europe were being laid. This small yet significant settlement first emerged into the annals of history, not with a roar, but with the quiet promise of growth and prosperity.

As the Middle Ages unfolded, Bad Mergentheim blossomed from a mere speck on the map into a bustling market town. Its fortuitous position on vital trade routes acted as the lifeblood of the town, pumping wealth and diversity into its streets. Merchants from distant lands, speaking in tongues foreign to each other, converged here, their carts laden with goods as varied as the landscapes they traversed. Silks and spices from the East mingled with the wool and wines of the West, creating a melting pot of cultures and commerce.

An anecdote that captures the essence of Bad Mergentheim’s medieval significance revolves around the legendary figure of Heinrich, a merchant known as much for his shrewd business sense as for his generous spirit. It is said that Heinrich, upon hearing of a harsh winter that had left many in the town destitute, opened his granaries and distributed grain freely, ensuring that none in Bad Mergentheim would go hungry. Such tales, perhaps embellished over time, underscore the community spirit that thrived alongside commerce.

The market square, with its cobblestone paths worn smooth by the passage of countless feet, was the heart of the town. Here, under the watchful gaze of timber-framed buildings, deals were struck, news exchanged, and friendships forged. The square was not just a place of trade but a stage on which the drama of daily life unfolded, from the jubilant festivities of harvest to the solemn processions of holy days.

As the centuries wore on, Bad Mergentheim’s strategic importance and economic vitality drew the attention of the Teutonic Knights, imbuing the town with a new layer of historical significance. Yet, even as the town grew in prominence and wealth, it retained its medieval charm, a bridge spanning the gap between the past and the present.

In crafting the narrative of Bad Mergentheim’s medieval beginnings, one is drawing not just from the well of history but from the very essence of human endeavor. It is a story of growth, resilience, and community, set against the backdrop of a world in flux. For the modern reader, these tales of yesteryear offer not just insight into the past but a mirror reflecting the timeless virtues of adaptability, courage, and unity.

Historical dates

1058 Mergentheim was first mentioned in chronicles as the,,Earldom of Merginthaim in the Tauber Region”

1340 Town privileges granted by Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria

1525 Mergentheim became the residence of the Grand Master

1809 By the order of Napoleon the Mergentheim territory was united with the Württemberg Crown

1826 The shepherd Franz Gehrig discovered the Wilhelm Fountain by the Tauber

1926 A century after finding the fountain Mergentheim received the official predicate „Bad” (bath)

Cultural attractions

Old Town Hall with tourist information

Built in 1564 by the Grand Master Wolfgang Schutzbar

Marketplace with twin houses and the Milchling fountain

The fountain is the city’s landmark

Cultural Forum at the Hans-Heinrich-Ehrler-Platz

Built between 1700 and 1702 as a secondary school for the Teutonic Order

St. Mary’s Church

Constructed in the 14th century by the Dominican Order, restauration 2015/16

St. John’s Cathedral

The cathedral was constructed between 1270 and 1290 by the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem

The Castle of the Teutonic Order

The residence of Grand German Masters from 1525 to 1809

Castle church

Built in 1730 1735 in the baroque style

Castle park

A park with artificial waterfalls, designed in the English style

Spa park

The spa park is among the most beautiful park areas in Germany

Walking and hiking

The 140-km-long hiking trails surrounding Bad Mergentheim will leave nothing to be desired. You can take a gentle ramble or a challenging tour, whatever takes your fancy. You can marvel at unspoilt nature and the eclectic history of the region along every single kilometre.

For shorter tours we recommend the circular walking trails around Bad Mergentheim. You can get a walking brochure for the circular walking trails, further information and detailed advice in the tourist information centre or from the resort administration.

Panoramic hiking trails

The local Panoramic Hiking Trail will guide you through the most beautiful spots with imposing views over the town and the Tauber Valley. The start and end point of the tour is the Galgenberg. From here you can go to the ruins of Neuhaus Castle, Nordic walking the former armoury of the Teutonic Order. In the nature reserve surrounding the castle, you can find the Wachholder-heide (juniper heathland)

which has been declared a natural monument. The route leads around Bad Mergentheim through the woodland areas of Ketterwald and Arkauwald.

Markers: signposts with a black P on a green background.

Length: 18 kilometer

Nordic Walking Bad Mergentheim offers two sign-posted routes. For beginners, there is the 1.8-km-long route without varying gradients. Starting from the Kneipp basin in the spa park, walk along the beautiful Säulen-Pappel-Allee through the castle park, then through the outer spa park to return again to the starting point.

The second route, which is 7.5 km long, requires more stamina. The route leads diagonally through the spa park and the Japanese Garden, leading steadily uphill towards Löffelstelzen. The return route leads through the Ketterwald and along Edelfingerstrasse, bringing you back to the spa park.

Cycling in and around Bad Mergentheim

For many active holidaymakers being out and about in the great outdoors is the ideal balance to our increasingly fast-paced daily life.

Due to its location in the lovely Tauber Valley and on the Romantic Road, Bad Mergentheim will make all your dreams come true.

Enjoy the journey through an idyllic hilly landscape, forests, meadows, fields and vineyards with the stone-layered hills typical of this landscape. Visit one of the many towers and castles of the Teutonic Order, or the Renaissance Palace in Weikersheim, during your trip.

Information and maps for the cycle paths on the Romantic Road and the lovely Tauber Valley or for the six circular routes around Bad Mergentheim are available in the tourist information centre.

Distances

Walkways starting at the Tourist Information

The Castle of the Teutonic Order 300 m about 3 min.

Railway station 500 m about 5 min.

Solymar Spa 1.200 m about 20 min.

Spa Garden (Spa Guest House) 700 m about 10 min.

Spa Administration 800 m about 11 min.

Wandelhalle 800 m about 11 min.

Caravan parking space 1.200 m about 20 min.

A Culinary and Cultural Odyssey through the Tauber Valley

The Tauber Valley, with Bad Mergentheim at its heart, is a region steeped in history, culture, and viticulture, a testament to the rich tapestry of German tradition. This picturesque landscape, cradled by rolling hills and dotted with historic towns, is not only a sanctuary for those seeking tranquility but also a treasure trove for enthusiasts of history, wine, and timeless German traditions.

Historical Attractions and Enclaves of Culture

Bad Mergentheim itself is a focal point of historical significance, with the Castle of the Teutonic Order standing as a majestic reminder of the town’s medieval past. This castle, which once served as the residence of the Grand Masters of the Teutonic Knights, is now a museum, offering a deep dive into the order’s history and influence in the region.

Nearby, the towns of Markelsheim, Edelfingen, and Tauberbischofsheim each contribute their unique threads to the valley’s historical and cultural fabric. Markelsheim, a quaint village nestled within the Tauber Valley, is renowned for its wine-growing prowess. The vineyards here, basking in the valley’s favorable microclimate, produce wines of exceptional quality, with local wineries inviting visitors to taste and learn about the region’s vinicultural heritage.

Edelfingen, with its rustic charm and scenic landscapes, offers a glimpse into the rural traditions of the area. Its proximity to Bad Mergentheim makes it a perfect spot for those looking to explore the countryside while remaining close to the spa town’s amenities and historical sites.

Tauberbischofsheim, a town rich in history and culture, is famed for its beautifully preserved medieval architecture. The town’s landmark, the castle, dates back to the early 13th century and serves as a silent witness to the town’s storied past. The old town, with its narrow streets and historic buildings, invites visitors to step back in time and experience the enduring legacy of the region’s history.

The Vineyards of the Tauber Valley

The Tauber Valley, cradled within the serene landscapes of Germany, is a verdant tapestry of vineyards that yield wines as diverse and captivating as the region’s history. This fertile expanse is home to a range of microclimates and soil types, each imparting unique qualities to the grapes cultivated here, and by extension, the wines produced. As you traverse the Tauber Valley Wine Route, the varietals and blends you encounter tell a story of tradition, innovation, and the relentless pursuit of excellence by the valley’s vintners.

Markelsheim’s Signature Wines

In Markelsheim, the sun-drenched slopes nurture primarily Müller-Thurgau and Silvaner grapes, resulting in wines that are both aromatic and full-bodied. The Müller-Thurgau wines here are celebrated for their subtle floral notes and a hint of nutmeg, offering a soft, yet complex palate experience. Silvaner, on the other hand, is cherished for its understated elegance, presenting a balanced acidity with whispers of green apple and fresh herbs. These wines epitomize the delicate dance between tradition and the characteristics bestowed by Markelsheim’s unique terroir.

Edelfingen’s Exquisite Varietals

Edelfingen contributes to the Tauber Valley’s reputation with its robust reds, particularly the Spätburgunder (Pinot Noir) and Dornfelder. The Spätburgunder from Edelfingen is a revelation in glass, embodying depth and sophistication with its rich cherry and berry aromas, underlaid by a subtle oakiness from careful aging. Dornfelder, known for its deep, velvety color and fruit-forward profile, offers a more accessible yet equally rewarding taste, with hints of plum and blackberry, accented by a touch of spice.

Tauberbischofsheim’s Diverse Palette

The vineyards surrounding Tauberbischofsheim are a testament to the diversity of the Tauber Valley, producing both red and white wines of distinction. Among the whites, Riesling stands out for its crisp acidity and stone fruit flavors, often with a mineral finish that speaks to the limestone-rich soils of the area. For red wine enthusiasts, Tauberbischofsheim’s Schwarzriesling (Pinot Meunier) is a must-try. Less known than its Pinot cousins, it offers a lighter body with nuanced flavors of red fruits and a pleasing finish, making it a versatile companion to the region’s cuisine.

The Winemaking Tradition

The Tauber Valley’s winemaking tradition is characterized by a harmonious blend of age-old techniques and modern innovations. Vintners in the valley are custodians of the land, employing sustainable practices to ensure that their vineyards thrive for generations to come. This commitment to quality and sustainability is evident in every bottle, from the hand-picked grapes to the meticulous vinification processes that coax the best out of every varietal.

Wine enthusiasts embarking on the Tauber Valley Wine Route will discover not just the exquisite wines but also the stories of the people behind them. The route is punctuated by family-run estates, historic wineries, and cooperative cellars, each offering a unique insight into the life of the region’s wine community. Tastings often come with the opportunity to meet the winemakers themselves, providing an intimate understanding of their craft and the passion that drives it.

A Tapestry Woven Through Time

The Tauber Valley, with its blend of history, culture, and viniculture, is a microcosm of German heritage. The region’s towns, each with its own story and charm, offer a mosaic of experiences that capture the essence of Germany’s past and present. From the architectural marvels of the Teutonic Knights in Bad Mergentheim to the vineyard-covered hills of Markelsheim, the valley is a journey through time, tradition, and the senses.

As visitors explore the historic streets, taste the local wines, and immerse themselves in the traditions of the region, they are not merely tourists but participants in a story that continues to unfold. The Tauber Valley, with its enduring legacy and living traditions, stands as a beacon of German culture, inviting all who wander its paths to discover the richness of its heritage and the warmth of its welcome.

Anecdotes from Gert's Apprenticeship: Tales from the Hotel Victoria

Alright, here are some anecdotes. At the start of my apprenticeship during Bad Mergentheim at the Victoria Hotel, the time I grew up in Germany, schools were set up so that you attended for eight years. After finishing, you learned a trade, which involved three years of working at the place and going to school. My choice was to become a cook. So, with my parents, we visited different hotels in the region to see if someone would take on an apprentice. Luck was on our side, and I ended up in the Hotel Victoria, which had a great reputation for their food. They served Bad Mergentheim, nestled in a lovely valley surrounded by vineyards and fruit orchards in the Tauber Valley. The name Bad in German means spa. The town was known for its healing waters, so almost everyone in town was somehow connected, working in the medical field or the hospitality industry. It was not a big town, but it was a hell of a lot bigger than the place I spent my childhood. The town was full of people getting their spa treatments, needed or not. The German state was booming; there was plenty of money in its treasury, so doctors handed out spa treatments like crazy. Anybody had any health problems? A spa treatment was prescribed. You got your prescription, what you needed to eat and drink, and off you went. Almost all the people I knew had treatments, including my parents and many of their friends.

So when the time came, I packed my few belongings, and my mother and I boarded the train for a 50-kilometer ride to my new life. I was scared and nervous, the first time away from home. Can I handle it? My mom brought me to the kitchen door, handed me over to the head chef, and she left. I was alone. I felt the world crashing down and it took all of me not to start crying. The last thing I wanted was for anybody to see how scared I was. But the chef was nice to me. I’m sure that a long time ago when he started, he must have felt the same way. Later, I found out that he grew up in the same region as my mom. He was a refugee from the eastern part of Germany. Growing up, I always had the feeling that, even though we were German, we were always outsiders in our village where our neighbors had lived with their families for hundreds and hundreds of years. Generation after generation, you just got treated differently. As a child, I was not aware of this, but I came to a full understanding later on in my life. So, coming from the same area as the head chef, he took a special interest in me, which did not mean that he gave me any breaks, but I always felt he kind of liked me and made sure I learned my trade well. However, I also learned very fast during my first conversation with him, sitting in his office, that he had a temper. The maître d’hôtel of the hotel came to the office door to make a complaint about a VIP. The maître d’hôtel was a gentleman in his early 50s, with greased black hair, a black tuxedo, manicured nails, a perfect mustache, and great posture. The first words out of the chef’s mouth were something I’ll never forget: “What would you like to know? You smell like a *****. And what the hell do you want?” The maître d’hôtel, obviously used to this abuse, did not seem to care one way or the other. The only thing he wanted to express was that the customer in question was an Arab and of Islamic faith and was not fond of his pork medallions because he did not ordered them. Then, the chef kept on ranting and raving with more profanity, which I do not care to share with my readers. Mel Gibson would be jealous of the choice of words the chef had in his invective vocabulary.

So here, for the first time, I experienced the love-hate relationship between the kitchen and service. Because when the day was done, most of the cooks and waiters got together for drinks and other mischief. My first day, I was told to be there at 7:00 AM sharp, fitted out with my cook’s jacket, pants, hat, scarf. I wondered about the scarf. What is it for? I was told it was because the constant going back and forth between the walking boxes, which were very cold, and the hot kitchen could give you a cold, which was unacceptable. After all, your meager salary and not being at work for 12 hours a day might put the hotel out of business. The main kitchen was hot, and their gigantic stove, which was the centerpiece, was glowing hot red. During service time, and on top of it all, most kitchens during this time were located in the cellars with no windows. It took me some time to get used to it. Slowly, the rest of the crew showed up. By 8:00 AM, all of them were there, and breakfast was served, usually coffee, bread, marmalade, which was the task of the apprentices, the lowest in the hierarchy of the kitchen. At first, I was verbally abused by all the older cooks. Even the older apprentices joined in, making you feel small and stupid. Chef Ramsay is tame compared to these guys. I was only 14 and scared. How would I be able to go through three years of such abuse? After they were finished, they started to insult each other or brag about their conquests, men about women, and women about men, and they were not shy in explaining it in the finest details. Nobody would get away with this sort of language today. And you also have to know that some of the chefs were females, but they were usually part of the conversation and could take it rather well. They were not afraid to give it back to them in the same tone of language. I had never heard that language before. My parents and in-laws never used those words. So, after a while, I got used to it and let it roll off my back. Not all of the cooks were jerks, and a few never amounted to much, and after all, I finished my apprenticeship, I never saw them again or was interested in any other way.

After breakfast, one of the older apprentices, who was one of the nicer ones, told me, “Let’s go to the linen room.” On the way over, he advised me, “Be quiet. Always say ‘Yes, chef.’ ‘No, chef.’ ‘What can I do better, chef?’ And you just do what you are being asked. If they scream at you, tell them, ‘Yes, chef. You are right.’ And never argue. The only thing you need to do is agree. If he says you’re stupid, just answer ‘Yes,’ and the trials will be over soon. But don’t forget, this kitchen is excellent. It is a great place for you to learn and then to get the hell out of here.” So, I picked up my apron and two hand towels, which were supposed to last you for two daily shifts, from 7:00 AM till 3:00 PM and 5:00 PM till closing, which could easily be midnight, six days a week. The kitchen brigade was classic, from the top, the sauce cook, to the poissonnier, entremetier, garde manger, and pâtissier. My first position was in the garde manger section, which consisted of a butcher shop, an appetizer station, and a salad station. Being the newcomer, the salad station was my task. My chef, garde manger, was quite a prima donna. He thought of himself as a ladies’ man. Well, I would say, if it’s in the eye of the beholder. Supposedly, he had an affair with both the pastry chef and another girl, both were his subordinates, because even as a novice, I could see that he was not that good. He never amounted to anything besides being a chef in a local cafeteria. Oh, but not him. He thought he was God’s gift to the cold kitchen. He constantly bitched about everybody under his command. During the four months, I never saw him take a whole pig apart, arrange or any of the whole other animals or make a pâté or fillet fish. The head butcher, in a rare outburst, told him, “If you don’t get the **** away from me, I’ll cut off your balls.” My first work consisted of cleaning all the different produce which was used in the cold kitchen. I can only laugh and be amused when I read and hear all the talk about “field to farmers to the kitchen.” What a joke. Everything we got during this time came from our local farms and was only seasonal. We never used one item of produce that was not fresh or harvested the day it came in, and it was carefully inspected by the chef.

So, this is what I had to do for a few months. After this, I was transferred to the entremetier station, which I always felt was one of the busiest in the kitchen, because that’s where all the side dishes are prepared: pasta, noodles, dumplings from bread, potatoes, and semmelknödel, at least three or four different potato dishes each day, either mashed or hand-carved, and an assortment of seasonal vegetables. It is one of the stations where you find out if you’ve got the right stuff to be a chef. You have to be fast, organized, and cool under pressure, and there you first learn how to use the knife. Everything has to be absolutely precise, nothing uneven, and the chefs constantly checked on you and made you do it over and over again until they were perfect. Everybody had time in the kitchen, participated in the task, and we had contests, to see who was the fastest and could produce more than anybody else. During my time at the vegetable station, the most memorable was the asparagus season in the month of May. The region of Schwetzingen produces some of the best white asparagus in Germany. We had a special menu for asparagus, since most Germans can’t wait for this delicacy. Each day we got two or three cases delivered, which we peeled only the bottom part and portioned into same-sized bundles, which were poached in water with salt and butter and served immediately on a folded white napkin on a silver platter with either fresh drawn butter or sauce hollandaise. There were no sides, but they were the main course. The chef, being a purist, explained to me that this is the only way it should be served, but to his horror, the public demanded other preparations as well. For example, with tomato sauce and freshly grated Parmesan. In his mind, what do Italians know about asparagus? Since they are wimps, and his experience during the war proved it to him. His steadfast belief was that the Italians lost the war for the Germans because they were horrible soldiers. And in their tanks, their display was they had all the gears into the rear. My God, he made it known to all the potential dishwasher, which were all Italian immigrants, and to him seemed like second-class citizens, and they got the wrath of him on a daily basis. You might want to know why Italians worked in Germany during this time. Germany’s economy was in full swing, called the Wirtschaftswunder, and they needed workers, and the first immigrants or so-called “guest workers” came from Italy, mostly from the southern part. Later on in life, I found out when I lived, traveled, and worked in Italy that Italians and Italy is a wonderful and beautiful country, which can be proud of its heritage and culture. After all, it gave us the Renaissance and the Enlightenment.

After six months of working my *** off on the vegetable station, I was transferred back to the garde manger station, the cold kitchen. I spent close to a year in this station. During this time, I was taught how to butcher, trim, and take apart any kind of animal. Our chef demanded that we only use the best of the best. Our beef was from Limbourg. These cows are known all over Europe and are even shipped to France because it was Napoleon’s favorite beef. Well, if the French thought it was good, it probably was. Because after all, during this time, almost all European hotels and restaurants practiced and served French cuisine, à la Escoffier. The pigs came from the region of Swabia, the Schwäbisch Haller pig, goat, sheep, rabbit, and poultry such as chicken, roosters, turkey, geese, and ducks came from local farms. During this time, I learned to take all these animals apart. The special cuts of meat like filet, rump, or legs were hung and aged in our meat lockers, and the Inards such as liver, kidney, brain were separated for specials, and the lesser cuts were cut up for stew, pâtés, or terrines. The only thing we did not do in-house were sausages and smoked or cured meats. The chef believed the art of charcuterie should be left to the master butchers. After all, if you ever visit a butcher shop in Germany, there are so many different sausages, terrines, pâtés, cured and smoked meats, it will blow your mind. Later on in life, the opportunity came for me to spend a few months in a great butcher shop, and I was able to see how it is done. It is one of the professions where experience counts. The owner of the shop told me, “I am never ever totally satisfied with the end product. I always try to make it better and better.” The quote always reminded me of my chef: “Never buy sausages from a butcher who drives a big, expensive car. He uses too much ice and fat in his sausage mix.” This was either jealousy or just one of his jokes. Well, it could make sense.

Let’s talk a little bit about seafood. Once or twice a week, we got fish delivered from Hamburg, which is a major port city at the North Sea. The fish market is one of the biggest ones in Germany, and one should visit it if you are in Hamburg. The boxes were filled with Dover sole, halibut, cod, salmon from Scotland or Norway, mussels, oysters, and lobsters from Helgoland, a small island in the English Channel. All the fish came whole, except they were gutted. It was amazing how fresh the fish was, perfect red gills, and clear eyes. They were filleted the day they were served. I remember the day well; I was putting the fish away in a nice bed of ice, sorting them out by species, and covering them with ice, using a wooden hammer to break the ice down. Not knowing what I was doing, I did not hear the chef coming. Red in his face, screaming, he picked me up from behind and dumped me into the ice bin, closing the door on top of me. The last words out of his mouth were, “Now, can you feel how the fish feels, you stupid little *******?” That was the kindest profanity I got an earful of at that moment, but then I got it. The last thing you ever do is try to bruise the fish. Fish is such a delicate species. Well, lesson learned.

Our other seafood came from the lakes, rivers, and streams nearby, like perch, carp, eel, and blue trout. Trout was always on our à la carte menu, but every Friday, we served it for lunch as a special, and 80% of the customers had trout, either meunière, which was sautéed golden brown in butter, topped with sliced lemon, fresh chopped parsley, and topped with the brown butter with a dash of white wine, or “au bleu,” which is poached in a court-bouillon with onions, carrots, leeks, white wine, and with a touch of white wine vinegar to enhance and preserve the blueness of the fish. This can only be achieved with live trout, which is killed minutes before poaching. The other important trick is not to disturb the slime cover around the trout when killing it, which is not an easy task. For Friday’s feast, the live trout was delivered in big oxygen barrels by trout farmers and quickly transferred to our trout tanks, where the trout had a few moments to breathe before being killed and served to the hungry customers.

Working in the cold kitchen and butcher shop, mind you, we never killed animals in the hotel kitchen. I wondered many times what God-given right we humans have to kill animals for our eating pleasure. Anthropologists theorize that when men discovered fire and first roasted meat or fish over the open flames, we started to socialize, and the protein was mandatory to develop our brain function and to progress. During this time, nothing of the animal was discarded. The hides were used for clothing and shelter. The farmers later in the life cycle used everything. For example, the cow gave milk, which is necessary for human consumption, to make yogurt, cheese, and butter. Look at the Hindu religion. The cow is sacred. You ask why? It is simple. It gives the gift of life, milk. The farmers in Europe use the cow not only for milk but for meat, and the hide for all kinds of leather goods. Or how about the geese? Not only are they a great roast, but the feathers keep us warm in now priceless goose down blankets.

During my childhood, I never saw farmers mistreat animals. They were cared for lovingly and respectfully. They were not in cages. They roamed free in the fields and meadows where they were butchered, and God was thanked at every meal for the bounty He provided. Like I mentioned before, at the hunt, each animal was honored with a different sound of the hunter’s horn. Where the killing of animals is not right is in the African bush, where lions, antelopes, or any kind of wild beast is killed for the sole purpose of the trophy. Or when elephants are butchered for their tusks, so some old rich Asian male can have a hard-on. Or when buffalo hunters destroyed the wild buffalo for the only purpose of their hides. I do not blame the American Indians for scalping the ********. For them, or the day’s consumer, which leaves half his food on the plate untouched, or demands a 16-ounce steak so he can stuff it into his obese fat *** when millions of people starve to death. Or modern agriculture, where animals are bred in such close quarters that they can’t move, where turkeys and chickens are in cages for the sole purpose of getting fat, stuffed with steroids and who knows what else. These poor animals can hardly stand up. That is wrong. Thank God, things are changing back to more humane raising of animals. So, before you open your mouth to stuff your face at our glorious fast food places, imagine the animal.

For my last eight months in my apprenticeship, I worked at the sauté station, also called “Saucier.” This station includes cooking fish, all meats, including poultry and shellfish. In some of the bigger hotels I worked later on in life, the station was split where we had a fish station, a steak station, a sauce station. These stations had the names of Poissonnier, Grillardin, Saucier, Chef de Viande, and Rotisseur for broiling and grilling meats and other things. Later on in my cooking life, the broiler man was very important, particularly in the United States.

Well, it was fun working at the station. Heinrich was the head of this department. He was strict but fair, and I learned a tremendous amount from him, and he was the person who gave me the right directions for my career. After my exams, which I took in both practical and at the school which I attended, my paperwork was completed, he told me, “Good. Now you’re ready to go. Victoria is enough. You’ve learned everything you can here. Now the world is your oyster.” And that’s what I did. We worked together a few times during my time in Europe, vacation times, or other times. He was first in the Stadthale in Weikersheim and then in Schwäbisch Hall, It was always fun working with him, and he came to visit me in Austin, TX, and just recently in Granada, Nicaragua. He was and still is one of my greatest inspirations in life. We became friends, and he definitely was my most important mentor in my career as a chef.

During my time in Germany, it was not only work. In the summer months, lots of time was spent in the afternoon breaks at the local pool, sunbathing, playing volleyball, and football. In the fall, we took long walks in the park, listening to local orchestras, having a cup of coffee which were nursed for hours since you could only afford one of them on your meager salary. These times were spent usually as a group of some of the apprentices, and the younger chefs talking about the other places they have worked like Switzerland, Austria, England, or even France. What they liked and disliked, we hardly talked about food. It was mostly about girls, music, and the nightlife of all these different places. During the late fall and winter months, our meeting place was an Italian café where we listened to records on an old jukebox to the songs of Bobby Darin, Ray Charles, and all the other music coming from America. I never, ever thought at that time that I would spend most of my life in the US.

And on a recent visit to Germany, I wanted to find out if the place still exists. And to my surprise, it was still there, almost the same as it looked so many years ago. And you know, at that time, I remembered the wonderful times spent there as a very young man, dreaming and fantasizing about my life to be. I don’t remember exactly what I was wishing for, but I never imagined I’d end up in America, marrying a very rich woman from a billionaire’s family, traveling all over the world, becoming famous and rich, losing almost everything, living in Nicaragua, and marrying the girl I was in love with in Aspen, CO. Sometimes I think my life was driven by the wind, wherever it would take me. I wondered, did I ever have a plan? Like Shakespeare said, “To be or not to be.” Well, let’s stop the daydreaming and go back to Germany. A couple of times a month after work, we drove towards Frankfurt, a town not far away, and listened to bands from England and the states, or went to different festivals. Lots of fun was had. The only pressure was work, and even though we were all young and optimistic, nobody was worried, even though the Cold War was in high gear. But America was our ally, and my dad always told me, “Don’t worry about the Russians. The only reason they beat us is simple. They got help from America.” And after all, President Kennedy told us, “Ich bin ein Berliner,” which some people interpreted as “I am a jelly doughnut.” Regardless, a picture of Kennedy was found everywhere in Germany, and the people loved him and his wife, Jacqueline. They were fantasy. The country was full of promise, and there was nothing we couldn’t overcome.

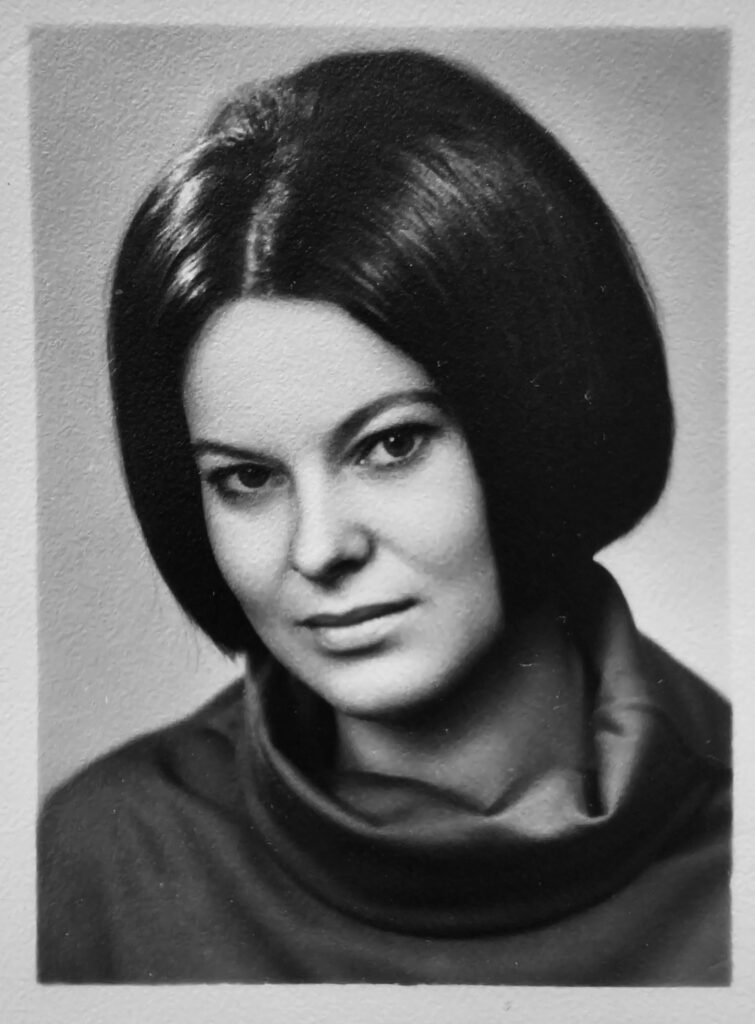

After 1 1/2 years into my apprenticeship, I fell in love with a beautiful girl. She was two years older than me and went to school before learning the hotel business and, being a woman, was well ahead of me, not only in education but in being mature. She was my first real girlfriend, and I still wonder today, what the hell she was doing with me. We spent a lot of time together, almost all the time which was possible at our work. I met her parents, and she met mine. Everybody liked her. It was definitely puppy love and probably my most romantic and as far away from reality as it is humanly possible. It was the only time in my life I ever thought about children. Even though the thought alone terrified me, I don’t think we ever fought. And after finishing our apprenticeships, we were both ready to conquer the world. And we both moved to the big city of Munich together. During this time, we lived in separate places. There was no way anybody would have rented you a small apartment as an unwed couple. We both worked very different schedules. The relationship took a toll. Even though we saw each other as much as time allowed, she was still my only love, but I could feel her slipping away. And getting a job in Switzerland was the end. Even a while before that happened, I was asked if I would mind if she dated other people, which I knew was the beginning of the end. It took me a long time to get over her, and walking around Munich by myself, seeing places we spent time together was very hard and lonely, and I could not wait to get out of town. I hope she had a wonderful life full of happiness and that it was fulfilling. I wonder what my life would have been should we have not separated? There are so many crossroads in life. I wonder, is your destiny planned out for you, or do you make it yourself? Like the Muslims say, “Inshallah,” God willing. I can definitely say that my apprenticeship was three years of learning about food, American music, standing on your own two feet, not even realizing it, creating a friendship with my teacher Heinrich and his wife, Loni, learning about life from the other cooks who already lived in other parts of Europe, reading cookbooks from around the world, working under sometimes brutal working conditions similar to marine boot camp, my chef screaming at me, making you feel like a nobody, thinking they can’t stand you. But when I said goodbye, he told me, “You came to me as a child, and I will let you into the world as a man. That’s all I can and will do for you. And I feel I did a good job. Go and go with God. And don’t come back.” So, after all the hard work and the abuse, I’m thankful to all the chefs with whom I worked during my apprenticeship. They were right in their own way. Cooking is a pressure job. No holidays, long hours, hardly any family life. When normal people get together to celebrate their weddings, birthdays, holidays, you as a cook serve them and enhance their happiness. That’s your job. An old French chef told me once, “You make their lives happy in their homes, the restaurants, their castles, but after all this, you will go home and live outside the castle. So you have two choices. You either love your job, which becomes your mistress, or you get the hell out of the kitchen.” Churchill had a good slogan: “If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” Scared but happy, my girlfriend and I went off to Munich. I went to the Bayerischer Hof, and she took a job at the Continental Hotel. We were ready to conquer the world.

Final Thoughts: The End of Volume I of My Apprenticeship

As I wrap up this chapter on the beginning of my apprenticeship, you might be wondering, “Where are all the cold kitchen recipes?” Well, let me assure you, there’s a wealth of them waiting for you. From mastering the techniques of cutting and aging meats to handling fish and crustaceans, from smoking fish and meats to preparing an array of cold sauces and soups, the cold kitchen is a treasure trove of culinary knowledge. You’ll also find recipes for crafting elegant cold appetizers and meticulously plated dishes, not to mention the art of making pâtés, terrines, and other intricate cold kitchen creations.

If you’ve enjoyed following my blog, I invite you to dive deeper by purchasing my book from my bookstore. It’s affordable—just a few bucks—and comes with easy steps to download. This book is not just a collection of recipes from my apprenticeship; it’s a comprehensive guide to the cold kitchen. Additionally, I’ve written a book about salads, aptly titled “Salads from the Cold Kitchen.” This book is a rich collection of salad recipes, not only from my early training but also from my extensive travels around the world. Each recipe tells a story, each dish a chapter of my culinary journey.

But my apprenticeship wasn’t confined to just the cold kitchen. I also gained invaluable experience at the Entremetier station, the bustling heart of vegetable, potato, pasta, and rice dish preparation. Here, I collected recipes from across the globe, each one a testament to the diverse culinary traditions I’ve encountered. The Entremetier station taught me versatility and the importance of precision, whether I was crafting a delicate consommé or a robust pasta dish.

Then there was the Saucier station, where I honed my skills in cooking and presenting meats, poultry, wild fowl, game, and seafood dishes. This station was a battleground of flavors, where the heat of the kitchen met the finesse of fine dining. It was here that I learned to balance bold flavors with delicate techniques, creating dishes that were as visually stunning as they were delicious.

I hope you’ve found my blog intriguing and that it has given you a glimpse into the life of a chef in training. My journey has been filled with challenges, triumphs, and countless lessons learned in the heat of the kitchen. As I continue to share my experiences, I hope to inspire you to explore your own culinary passions.

Stay tuned for more stories, recipes, and adventures in future volumes. Each new chapter will take you deeper into the world of professional cooking, offering insights and recipes that can elevate your home cooking to new heights. Whether you’re a budding chef or a seasoned home cook, there’s something for everyone in these stories and recipes.

Thank you for joining me on this journey. Grab your copy of “Apprenticeships: Starting with the Cold Kitchen” and start your own culinary adventure at home. Dive into the world of cold soups, canapés, and smoked meats, and discover the joy of creating beautiful, delicious dishes. Happy cooking!

With every page, every recipe, and every story, you’ll not only learn the techniques but also the heart and soul of what it means to be a chef. So, here’s to the start of your culinary journey—may it be as rich and rewarding as mine. Cheers!

Final Thoughts

Embarking on a culinary journey is more than just mastering techniques; it’s about understanding the passion, the sweat, and the stories behind every dish. My apprenticeship was filled with challenges, laughter, and learning, and I hope this book offers you a glimpse into that world. As you explore these recipes and stories, remember that cooking is an art that comes from the heart. Embrace each challenge, savor each success, and keep the flame of your culinary passion burning bright. Thank you for being part of this journey. Bon appétit!